Meet Morris Henry Wilson, a Michigan boy who enlisted in the Navy at the age of 15 — he told them he was older — and went missing on a submarine that never finished its maiden voyage in the fall of 1943.

Morris was one of my mother’s older brothers. It was a big, troubled, poor family in rural Michigan, a good situation to get away from if you got the chance. He took the chance. My mom never spoke much about Morris, nor did I ever ask her siblings about him. So I can’t tell you anything about his life before enlisting. In honor of Memorial Day, I’ll share what I know about the very brief remainder of his life. Which is pretty much entirely from official records.

By World War II standards, his death was random and inconsequential. He didn’t die in an act of heroism, unless you think the idea of a 15-year-old going to war is pretty damn heroic. I wouldn’t disagree. He died far from any active theater. The cause of his sub’s sinking has never been fully established; the most likely cause was friendly fire. Or it may have hit a German mine near Panama. Either way, the sub was never found and all 77 aboard were presumed dead.

The USS Dorado was built in 1942-3 at the naval shipyard in Groton, CT. After launch, her crew engaged in sea trials. Two American artists, Thomas Hart Benton and Georges Schreiber, had been commissioned by the Navy to capture life on a submarine; they accompanied the Dorado during its shakedown cruise. Each later painted a series paintings based on what they saw there, including Benton’s Score Another for the Subs:

The vessel was formally commissioned in August 1943. On October 6, it set off for the Pacific Theater with a first stop at the Panama Canal Zone. She was due to arrive on October 14, but never did. Afterward, air searches were conducted, but nothing was found besides a few oil slicks and some debris, which may or may not have come from the Dorado.

On October 12, Navy bombers based at Guantanamo Bay were providing protection for a convoy. The air crew were informed, as accurately as possible, about locations where Navy ships were likely to be located. In the Dorado’s case, the information might have been faulty. The bomber crew spotted a submarine near the convoy and dropped three depth charges and one bomb. They claimed to have positively identified it as a German U-Boat, but that may have been wishful thinking; the encounter happened at night, and nobody wants to think they hit one of their own vessels.

Another version: a week before Dorado’s scheduled arrival in Panama, German U-Boats laid a minefield in the waters off a Naval submarine base in the Canal Zone. Morris’ sub may have hit one of them. The mines were cleared by the Navy two days after the Dorado went missing.

A Naval Court of Inquiry ruled that no final determination could be reached because of a lack of evidence. The fog of war.

There is one other possibility, accompanied by a tantalizing bit of sea lore. In 2018 The Day, a newspaper in New London, CT, published an account of the Dorado’s brief life that included this passage: “In the early 1970s, cargo pilots flying off Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula used a landmark they called the ‘Gray Ghost’ to tell them they were approaching their destination. It was an object sticking up from the sandy bottom in shallow water, and when the sun was low in the sky, it cast a long shadow.

“It appeared to be the conning tower of a submarine.

“The Gray Ghost… later vanished beneath the shifting sands.”

Pure speculation: If the Dorado had been damaged but not sunk, prevailing ocean currents would have taken it near the Yucatan.

Barring a dramatic stroke of luck, we’ll never know. The loss of the Dorado was a footnote in the history of the war; it was a ship that never saw battle, never got within thousands of miles of any real fighting. Its reported loss was noted in The Day.

On page 12.

Big news, that.

The Dorado was one of only 52 U.S. submarines lost during the war, and one of only two lost in the Atlantic Ocean. The crew, my uncle included, are memorialized in at least two locations. The East Coast Memorial in Manhattan’s Battery Park is a series of stone markers inscribed with the names of all American servicemembers lost in the Atlantic Ocean. I was recently in New York City and went to the Memorial to pay my respects, but the stone with Morris’ name was walled off for a construction project. Maybe next time.

Or maybe I’ll find myself in Wichita, Kansas for some reason. There is a memorial to the Dorado, listing all its crew, in that city’s Veterans Memorial Park.

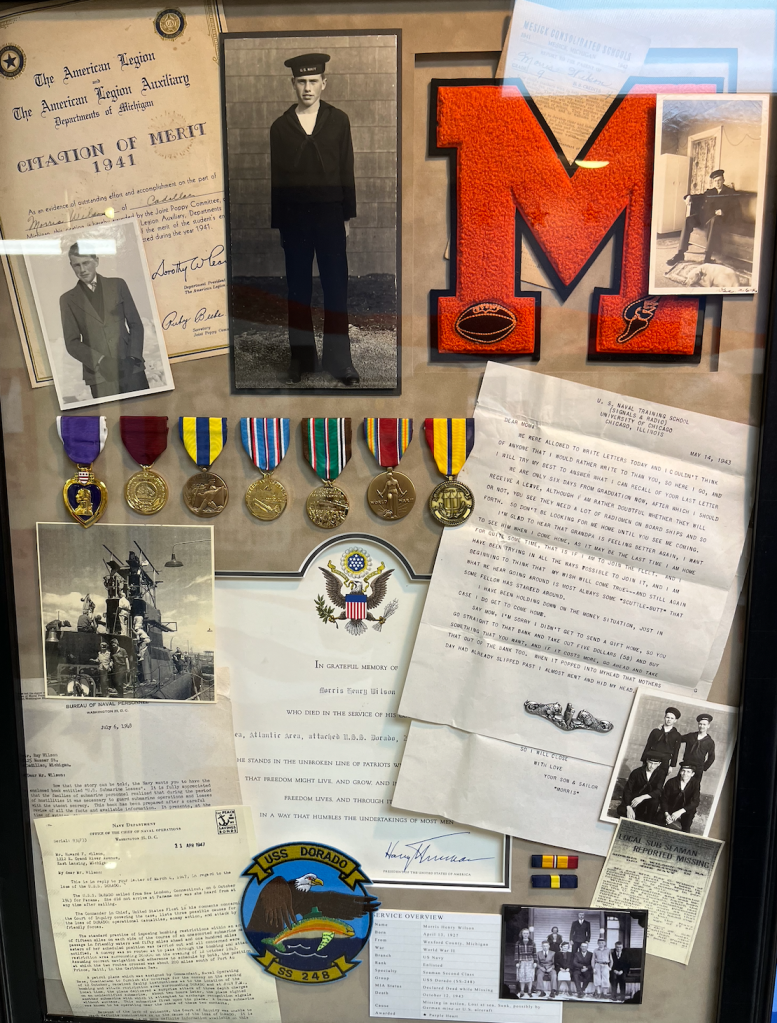

There’s also a more personal memorial on display in Cadillac, Michigan’s City Hall. One of its hallways holds a series of tributes to local residents lost in war, one of which was made in Morris’ memory by members of the Wilson family. I did get a chance to see this during a trip to the old stomping grounds last summer. Very glad I did. And very sorry I never took the chance to find out more about the uncle who gave his life in the war.

Thank you for sharing.

Very moving and bitterseet story. It is nice to be reminded what the holiday is really for.

I had an uncle like that. He was my mother’s brother. He was an army ranger in the Italian campaign. He came home from it, wounded, and I was very young when the war got him some twenty years later by his own hand. I only learned about him, about who he was, after he was long gone. War is such a colossal waste of life, more often than not for nothing.