This Just In: According to the Phil Scott administration, the Phil Scott administration is a terrible place to work. This is the implicit conclusion of the Department of Human Resources’ Workforce Report, whose most recent edition covers fiscal year 2023.

The report doesn’t offer that conclusion, but it’s the inescapable takeaway from its pages full of facts, figures, charts and tables. They show a state government that’s experiencing very high employee turnover and having trouble hiring new workers. it all adds up to unsustainably high vacancy rates in many areas of state government.

All those empty positions have a tangible benefit for the Scott administration, whose FY2025 budget is “balanced” only because it banks on the savings from having so many positions unfilled.

As for what this is doing to the quality of government services, well, it can’t be good.

The Workforce Report was released on January 12 to no notice whatsoever. It’s only come to light now thanks to Rep. Tristan Toleno of the House Appropriations Committee. As part of his work on the FY2025 budget he took a dive into the report. He then shared his findings with the Legislature’s other Tristan, Rep. Tristan Roberts, who wrote it up in a short and devastating opinion piece published by VTDigger.

On March 4, almost a month ago. I’ll admit that I missed it at the time, generally having little use for Digger’s opinion section. But it raises questions that deserve full scrutiny, and I’m here, belatedly, to do my bit.

Before we get to the depressing statistics, it must be noted that state government jobs ought to be pretty darn attractive. The pay is solid, the benefits are hard to beat, and workers have strong union representation. There should be an ample pool of applicants and retention shouldn’t be an issue.

To start at the entry point, the number of unique applications for state jobs has fallen from 18,778 in 2019 to 12,690 in 2023, a decrease of roughly one-third. Almost three-quarters of all openings had fewer than 10 applicants. And only about three-quarters of those offered a job actually accepted. Taken together, it means that something is making state government positions look unappealing to potential employees, even when a position is within their grasp.

But that’s not the bad part. Roberts:

Once hired, 10% of state workers don’t make it beyond 30 days at their new job, according to Gov. Scott’s most recent Workforce Report. Over 26% don’t make it to the six-month mark and 40% don’t make their first anniversary.

According to the Workforce Report, the state’s worker turnover rate was 13% in FY2022. That was a slight improvement from FY21’s historic 15.3% turnover, but was still the second highest rate ever recorded by DHR. (The decline from 15.3% to 13% was mostly fueled by a significant drop in retirements, not by any real improvement in worker retention.)

The report includes a chart that tracks turnover through a 25-year period, and there’s a clear pattern. In the final years of Howard Dean’s governorship, annual turnover was between 7-8%. During the Douglas and Shumlin administrations, annual turnover was usually in the 8-10% range. In Phil Scott’s first year in office it was 9.6% — but in four of the last five years, it was above 12%.

To put that in plain language, one employee out of every eight has left state government in each year of the Scott administration.

Toleno calls it “churn and burn,” and it has a corrosive effect on a workplace and the quality of its work product. It’s no surprise that some of the most troubled precincts of the administration have had the highest turnover rates.

The entities with the highest five-year average turnover are the Vermont Veterans’ Home at 23.8%, the Department of Corrections at 21.5%, and the Department of Mental Health at 20.8%. Those with turnover in the teens include Military, Public Safety, Human Services, Buildings & General Services, and Liquor & Lottery. At the very bottom of the list is the Agency of Administration at a mere 2.7%. Must be some comfy office furniture on the Fifth Floor.

When you turn to vacancy rates, you see the same pattern: High rates in problem areas of government. Mental Health has vacancies in more than one-third of its positions. At the botch-prone Department of Labor, 20% of all positions are vacant. The Department of Corrections’ vacancy rate is 16.6%, which is a substantial improvement from mid-2022’s 30.4%. DOC brought down the rate with offers of recruitment incentives and higher pay, but it remains unsustainably high.

Seventeen percent of positions in the Vermont State Police are vacant, not exactly a good look for a governor supposedly focused on crime. And the Department of Children and Families, which has been struggling to keep homeless Vermonters in shelter, has a vacancy rate of 10%.

Here’s an unfortunate little nugget from page 41 of the report: the turnover rate among underrepresented racial and ethnic groups was almost twice as high as among white employees. Which means those groups are now even more underrepresented than they were before.

According to Toleno, the governor’s FY25 budget took fiscal advantage of high vacancy rates by banking $57 million in savings from positions left empty. As I said of the governor’s awful temporary shelter plan, “If you build it terribly, they won’t come.”

In this case, if you have a terrible work environment, people won’t come. And if they do come, they don’t stay.

Why, indeed, does nobody want to work for Governor Nice Guy?

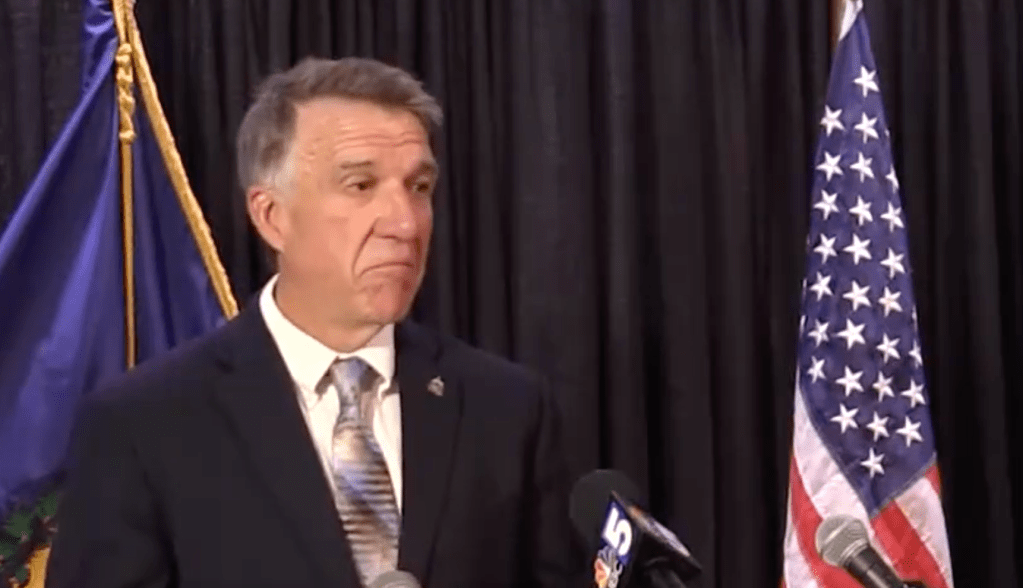

The pictures of Gov Scott, the pictures!

“If you build it terribly, they won’t come.”

I wonder if this is a deliberate attempt promoted by various lobbyists from private concerns to drown state government in a bathtub to privatize it and reward the biggest donors.

How do these stats compare with those in Vermont NGO and private companies?

“Why don’t Vermonters want to work for Phil Scott?”

Because he’s a FECKLESS CUNT!