Apologies for my extended blogging absence, but I’m just back from a long weekend in Montreal. There were a couple things on the must-do list; a performance by the Montréal Symphony Orchestra that was one of the best concerts I’ve ever attended (conductor Rafael Payare, a native of Venezuela, is a treasure), and the biggest single exhibit ever mounted of Kent Monkman, who’s an extraordinary craftsman and storyteller on canvas. It’s on display until March 8 at the Montréal Musée des Beaux-Arts, and I strongly recommend you make the trip if you can.

Monkman is a First Nations (Cree) artist who creates monumental canvases that remix the tropes and styles of Western art, inserting narratives that center the native peoples of North America. In the process, he exposes the unspoken social and political messages of “non-political” Western art.

Mounting this exhibition is a major accomplishment for Monkman and the MMBA, but given the fact that it took years of planning and effort, no one could have foreseen just how devastatingly apropos it would be in this historical moment. Seeing centuries of white colonials violently suppressing and attempting to erase Native people and culture, at a time when our government is conducting a taxpayer-funded war on brown people, makes Monkman look like not only a world-class artist, but a prophet as well.

So yeah, it’s worth a visit.

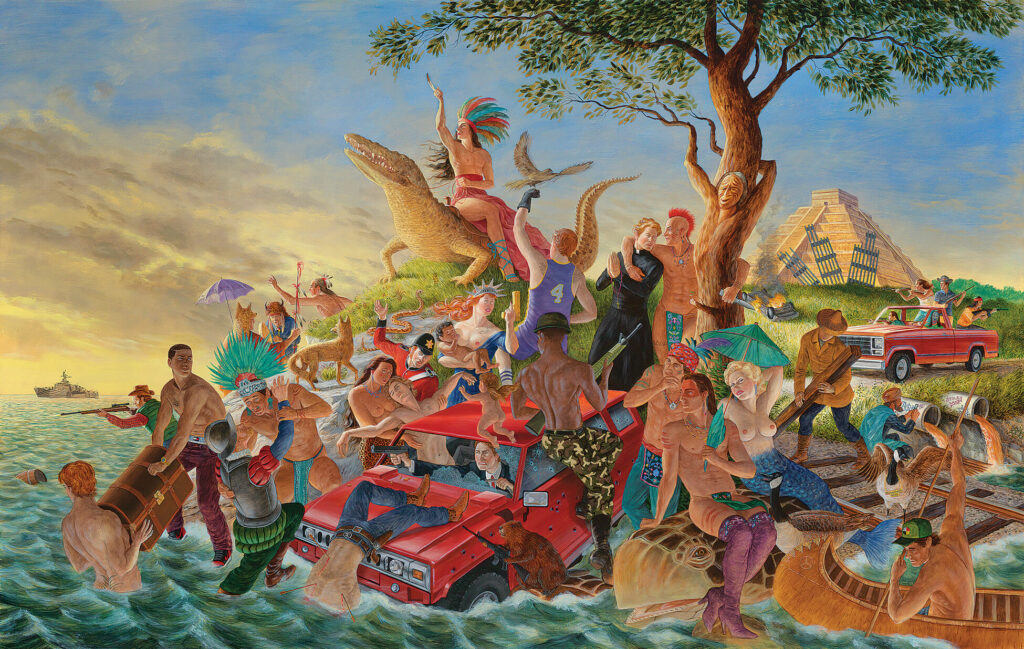

The image at the top of this post does not do justice to the original, which is a massive 7 by 11 feet. It’s rich in detail too small to see clearly; you can see a much larger image plus some close-ups here. It’s just… wow. The longer you look, the more you see. The MMBA exhibit encompasses several rooms of powerful, large-scale paintings like this.

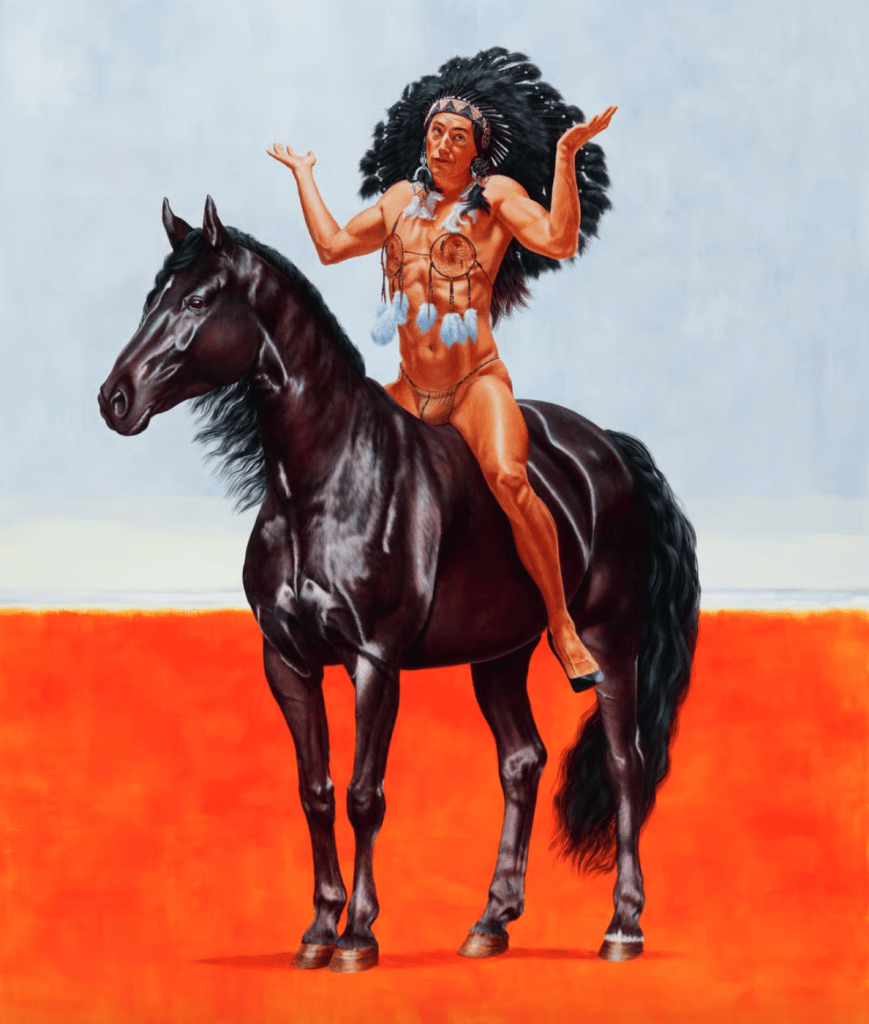

Rising above the scene is Monkman’s alter ego, the two-spirit Miss Chief Eagle Testickle, who appears in many of Monkman’s paintings as guide, artist, silent commentator, or liberator.

Many of his canvases are reworkings of monumental American or Canadian paintings from the 19th Century which, in his view, served as visual propaganda for the occupation of North America. Those landscapes are wild, engaging, and completely lacking in any acknowledgment that there were people here before the occupation began. The artists did not include the harsh realities of what happened to the native peoples in the process.

One room contains several paintings about the genocidal Canadian policy of forcibly displacing First Nations children to residential schools where they would be, ahem, “civilized.” That room contains a small, curtained reflection space for those overwhelmed by the images on display. And they are pretty damn overwhelming.

Other Monkman paintings depict the First Nations protests over the routing of fossil fuel pipelines through their lands and the violent response from police officials. Seeing those images a matter of days after the murder of Renee Nicole Good was devastating.

And it indirectly reflects a tough reality: Donald Trump is right, in a way. His immigration crackdown and his mean-spirited policies toward transgender folk (among many others) do, actually, represent a return to a past America. Because America has always been at war with itself — a beacon of democratic ideals on one hand, and on the other a brutally oppressive superpower that excludes anyone who’s not white, male, and affluent from enjoying our ideals.

It’s a question of which America you want to be. And seeing the same history, the same split personality, in Monkman’s art is a stark reminder of the burdens we all carry and the long trail we walk toward justice.

Through all of Monkman’s work there is a spark, a flicker of light piercing the darkness. Whether it’s Miss Chief calmly surveying (and subverting) scenes of colonialism or the people in his paintings determinedly surviving official violence, Monkman shows an inextinguishable quality about the human spirit, something no amount of oppression can wipe out.

I’m not an art critic or scholar, and I’m sure i got some stuff wrong in this post. But the Monkman exhibit had a profound effect on me, and I hope I’ve managed to convey some of that to you. And I hope you get a chance to see it in person.

Next time, I’ll get back to Vermont politics.

Monkman had an impressive exhibit with at least some of these at the Hood in Hanover recently.